Introduction

The discovery of paradoxes and inconsistencies in set theory during the early 20th century motivated mathematicians to more carefully study the nature of formalized mathematics; they began to ask what 'formalization' even meant, how mathematics could be formalized, and what the limits of formal systems were. The study of these questions led to the invention of abstract systems of computation, and in turn, the field of computer science itself. The lambda calculus was one such system of computation invented by Alonzo Church in the 1930s. It remains central to the theory of programming languages and forms the basis for modern functional languages like Haskell and OCaml.

I was first exposed to the lambda calculus during a programming languages course I took at college during fall 2024; this was probably my favorite course I ever took during my time at university. Besides theoretical topics like the lambda calculus, the course also discussed some modern programming languages such as Rust, which features an ownership type system designed to guarantee memory safety without the overhead of runtime garbage collection. I thought a fun way to revisit some of the concepts we covered in this course would be to build an interpreter for the lambda calculus in Rust; this blog post discusses some of the things I learned along the way :)

You can find the source code for the interpreter here.

The next couple of sections of this post provide some background information on the lambda calculus and Rust. However, if you're unfamiliar with these topics and would like to learn more, I'd highly recommend Stanford's CS 242 slides, the Rust book, and a textbook I found called The Implementation of Functional Programming Languages.

The Lambda Calculus

Syntax

Programs in the lambda calculus are composed of variables, function definitions, and function applications. Function definitions are written as ; this defines a function that given an input, returns where every occurrence of inside is replaced with the input that was provided. We use currying to represent functions that require multiple arguments. For example, if we have a function , we can write this as . This defines a function that given an input returns another function which, when given the input , returns the value . Function application is written as (this denotes that we apply the function defined by to ). Parentheses can be used to specify association. By default, we will have lambda abstractions bind to as much of the string that follows as possible, stopping only at the end of the string or a closing parenthesis that was not previously opened inside the lambda. This means that the program should be interpreted as . Additionally, function application will by default be left-associative; i.e. should be interpreted as .

Here are some example programs:

-

- The expression in parentheses (), is a function that takes in two arguments and , and always returns the first argument .

- We apply this function to and , so the the program will evaluate to because was bound to .

-

- This is a function that given another function and an argument , directly returns .

- Whole numbers can be encoded in the lambda calculus using 'Church encoding', which represents as a function that given a function and an input , returns the result of applying to a total of times.

- Thus, the above function corresponds to the number in Church encoding.

-

- This function takes in a whole number in Church encoding. It returns a function that takes in an argument , an argument , and produces as output the expression , which corresponds to applying one more time after applying it times to .

- Thus, this function computes given ; it is the 'successor' function for whole numbers.

Computation Rules

Now that we know how to write lambda calculus programs, how do we execute them? Execution involves repeatedly applying a set of computation rules. The most important of these is beta reduction, which says that when we have a lambda abstraction applied to some lambda expression, we should substitute the lambda expression for every occurrence of the lambda abstraction variable in the lambda abstraction body. The parts of a program where we are able to apply beta reduction are called redexes. For a concrete example, consider the expression . We see that the expression is a function application, with the function being a lambda abstraction. Thus, this is a redex, i.e. this is an expression to which we can apply beta reduction. To do so, we will substitute the input for every occurrence of the formal parameter in the lambda abstraction body. This gives the result . Since we no longer have any redexes, we have finished executing the program, with being the final result.

There is a complication with beta reduction, however. Consider the following program:

If we applied beta reduction 'naively', we would produce the following string:

This string represents a function that given some input y, returns the output of applying y to itself. However, this is not what the original program actually represents. The value to which we applied was a free variable; it was not bound by any lambda abstraction. We can rename the formal parameter to get an equivalent program , which when reduced gives us . The resulting function takes in a new argument , and applies the original free variable to it; this has a completely different meaning than , the string that we obtained when we naively applied beta reduction.

The problem is that in the naive case, the expression we are substituting for contains free variables that are bound by inner lambda abstractions of the expression we are substituting into. This issue is known as variable capture. To avoid variable capture, we will use another computation rule called alpha conversion, which just specifies that when we detect any instances where variable capture will occur, we will rename the formal parameter to prevent it. In other words, we will make sure to detect whenever we are performing a reduction like , and when we do, we will rename the lambda abstraction to be instead.

Reduction order

Two natural questions arise from the above discussion: (1) in what order should we reduce redexes, and (2) when do we stop applying computation rules? My implementation reduces expressions using the call-by-name reduction order until the expression is in weak head normal form.

Call-by-name evaluation evaluates an expression only when it is actually used. For example, let's say that we have a program that looks like . Under call-by-name, we will first substitute every instance of inside with without first evaluating ; will only be evaluated when its value is needed for some computation inside . This is in contrast to call-by-value reduction order, which would first evaluate before performing substitutions into . Another way to understand call-by-name evaluation is to see that it always reduces the uppermost, leftmost redex first while evaluating a program.

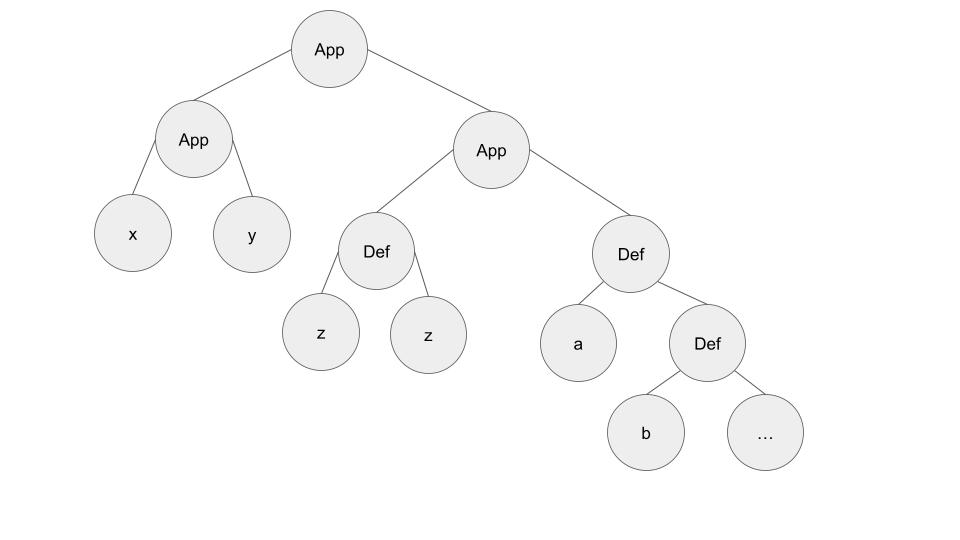

Weak-head normal form (WHNF) means that a lambda expression has no redexes along its 'left spine'. For example, consider the lambda expression . We can think of this program as a tree that looks like the following:

The left spine of the expression consists of the nodes on the far left side of the image, namely, the two function applications and the free variable . Since there are no redexes along the left spine, we will consider this expression to be fully evaluated. Note however that there are still redexes that could be reduced in the right subtree of the root node. An alternative to WHNF is normal form, which specifies that the expression contains no more redexes whatsoever, and would require us to reduce the redexes in the right subtree as well. It's possible that normal form evaluation might cause us to evaluate some expressions that never get used, so my implementation only reduces expressions to WHNF; for a similar reason, some real-world languages like Haskell also adopt WHNF semantics.

A common optimization in functional languages is to implement sharing, which tries to reduce the number of times we need to evaluate the same expression. The key idea of sharing is that when we perform substitutions, instead of substituting each instance of a formal parameter with a new deepcopy of its associated expression, we instead replace all instances of the formal parameter with pointers to a single copy of its associated expression. Now, if we ever evaluate any single instance of the formal parameter, we can reuse the results of that evaluation anytime that it's needed instead of re-evaluating the expression from scratch.

For example, consider the program . Under regular lazy evaluation, we would apply computation rules like so:

With sharing, the evaluation of the program would look like this:

As you can see, the evaluation of is shared between both instances of , so in the final output, is evaluated to the value in the term that is given as an argument to .

Sharing does slightly break the semantics of WHNF because it now might look like some extra expressions were evaluated as compared to true WHNF execution. This is not an issue for two reasons:

- The Church-Rosser theorem states that the lambda calculus is confluent, i.e., given that and , there must exist some such that and . Thus, even though the exact output strings produced with sharing may look different from those produced by exact WHNF evaluation, they will still be in some sense 'equivalent'.

- Sharing provides significant efficiency benefits when evaluating lambda calculus programs, and these gains are large enough to warrant violating the 'pure' definition of WHNF.

Now that we know what call-by-name, call-by-value, and sharing are, why would a language choose to implement one or the other?

The main potential benefit of call-by-name is that we might not have to evaluate expressions that we do not end up using. In the extreme, this means that for some programs, call-by-name execution might successfully terminate, while call-by-value execution loops forever while trying to evaluate a sub-expression that isn't actually used to produce the final result but that does not terminate. In fact, it can be shown that if any reduction order for a program terminates, then call-by-name evaluation will also terminate.

For example, consider the program . Under call-by-name evaluation this will reduce to:

However call-by-value evaluation will enter into an infinite loop trying to evaluate the sub-expression :

Despite call-by-name allowing us to skip evaluating unused expressions and having advantages in terms of termination, it has some issues that make it less practical for real-world languages. For one, we need to keep pointers to the code needed to materialize unevaluated arguments (called 'thunks'), which adds overhead. Furthermore, call-by-name also requires sharing to be practical because otherwise we might be doing a lot of deep copies when substituting a formal parameter for an expression. Another drawback of call-by-name is that it can lead to execution order / program behavior that is unintuitive to the programmer. This is an especially big problem if the code includes side-effects that are outside the bare-bones conception of functional languages (such side-effects could include interacting with IO, the filesystem, raising exceptions, etc). For these reasons, most languages implement call-by-value evaluation order, but for this project I chose to stick with the 'theoretically cleaner' semantics of call-by-name evaluation.

Rust

Rust is a programming language that prioritizes safety and performance. Its flagship feature is its 'ownership' system, which is designed to minimize memory errors common in C/C++ (double-frees, use-after-frees, memory leaks) while avoiding the overhead of garbage collection.

When a Rust program is executing, data is produced and stored in memory (call such data values). In Rust, each value is associated with an owner. Owners can be:

- Variables (most common).

- Formal parameters of functions.

- Containers like structs, enums (Rust's name for algebraic data types), tuples.

Note that both values and owners are dynamic; they are produced and change as a program executes. However, Rust enforces certain ownership rules statically to ensure memory safety. These rules are:

- Each value has an owner.

- There exists only one owner of a value at any point during execution.

- When program execution proceeds to a point where, for some value, its owner is no longer associated with an identifier in the code (i.e. the value's owner has gone out of scope), that value is deallocated.

So far, this sounds pretty simple -- we deallocate values when they go out of scope. The catch is that values might be aliased; multiple variables might refer to the same data during execution. We need a way to pick one of them as the unique owner, and ensure that it is not possible to continue to use the other variables referring to that value when the owner goes out of scope.

To resolve this, the programmer implicitly tells the Rust compiler which variable / function parameter / container is the unique owner of some value in the program they write. The other variables through which that value can be accessed are references. References borrow values from their owners, and when a reference goes out-of-scope, the underlying value is not deallocated (deallocation only happens when the owner goes out-of-scope). References are basically pointers, but Rust's ownership / borrowing rules guarantee that they will always point to valid memory. Here's a small example:

fn print_str(x: &String) {

println!("x is {x}.");

}

fn main() {

// test_x_1 is the owner of the string.

let test_x_1 = String::from("Hello");

// Assignments have 'move semantics' in Rust. Here, ownership of "Hello" is

// transferred from test_x_1 to test_x_2, and test_x_1 is no longer usable.

let test_x_2 = test_x_1;

// This line would throw an error since ownership was transferred to

// test_x_2.

// println!(test_x_1);

// We call print_str with an immutable borrow of test_x_2.

print_str(&test_x_2);

}

To make sure that references always point to valid memory, each reference is associated with a lifetime. A reference's lifetime is the region of code where it can be used. Rust's borrow checker infers lifetimes for all references in a program and makes sure that every reference's lifetime does not exceed the lifetime of the value's owner (programmers might have to specify some lifetime information manually though, particularly at function calls and when defining structs).

Interpreter Overview

When users run the interpreter, they specify a single source code file to run the interpreter on. The interpreter reads the file into a string, lexes it into a vector of tokens, parses the vector into an AST, and finally executes the AST. The execution engine applies reduction rules in lazy / call-by-name order until the given AST is in WHNF.

Despite its benefits, I chose not to implement sharing as I wanted to focus on keeping the implementation as conceptually simple as possible. For the same reason, I didn't implement another optimization called De Bruijn indices which would remove the need for explicit alpha conversion. Implementing sharing and De Bruijn indices are two important extensions I hope to make on this project in the coming months.

Language Syntax

Here's a short program that demonstrates the key syntax of the language that the interpreter accepts:

// Example of Church encoding of whole numbers.

def zero = \f. \x. x;

def succ = \n. \f. \x. f (n f x);

def one = succ zero;

def two = succ one;

eval zero f x;

eval one f x;

eval two f x;

The interpreter will produce this string as output:

x

f (zero f x)

f (one f x)

As you can see, users can add comments with '//'. The program consists of a sequence of def statements and eval statements. Eval statements are the lambda expressions that the interpreter will actually execute. Def statements essentially function as macros. As the interpreter executes an eval statement, if it ever needs to evaluate a variable that looks like a free variable, it will first check if there is a def statement that maps that free variable name to some sub-expression, and if so, the interpreter will substitute that sub-expression into the eval statement and continue execution.

Lexer and Program AST Representation

The interpreter has three main stages: lexical analysis, parsing, and code execution. As part of lexical analysis, the input program string is turned into a sequence of tokens, each of which belongs to some 'token class'. Some token classes include 'whitespace', 'comment', 'identifier', and 'lambda'. The implementation of the lexer is fairly simple. Each token class is associated with a regex, and given an input string, the lexer emits the token that matches the greatest number of characters beginning from the current start of the string. After emitting this token, the starting index is incremented, and the process repeats.

The sequence of tokens produced by the lexer is then consumed by the parser. The parser converts the token sequence into a data structure called an abstract syntax tree (AST). This AST is later used during code execution.

I chose to represent the program AST for a lambda expression as a collection of heap-allocated 'ExprNodes', with each node having a unique pointer to its descendants in the AST. Here is a snippet of code from the codebase defining these nodes:

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq, Clone)]

pub enum ExprNode {

FnDef {

formal_param: String,

fn_body: Box<ExprNode>,

},

FnApp {

fn_body: Box<ExprNode>,

actual_arg: Box<ExprNode>,

},

Var {

var_name: String,

},

}

This program representation is extremely simple. Using unique Box pointers is a natural fit in this case since I chose not to implement sharing, but when I do implement this, I'll likely have to switch to using Rust's Rc<T> type instead.

Parser

The parser is a simple recursive descent parser (a fancy way to say backtracking search on grammar production rules). You can read more about recursive descent parsing in Stanford's CS 143 slides or the Dragon Book.

Determining the exact grammar to implement in the parser took a little bit of iteration. Here's a first attempt :

Unfortunately this grammar is ambiguous. There are two problems:

- Consider the expression . Should this be parsed as , or as ? In other words, what is the scoping for lambda abstractions with respect to the string that follows?

- Consider the expression . Should this be parsed as or ? In other words, what is the association for function application?

As mentioned before, we want to have lambdas bind for as much of the string that follows them as possible, and we want to have function application be left-associative. Another constraint to keep in mind is that since we are using a recursive descent parser, we need to make sure that the grammar is not left-recursive.

Here's the grammar I ended up implementing:

To resolve the ambiguity with lambda abstractions, note that we want to invalidate the derivation in our original grammar, because in this case the lambda abstraction does not bind for as much of the string as possible. The above grammar does this by introducing a new nonterminal called , which represents expressions that do not start with a lambda abstraction. When we now have chains of function applications like , these will have to be generated by a derivation that looks like

Since can never start with a lambda abstraction, we will no longer have any of the lambda abstraction ambiguities possible with the initial grammar.

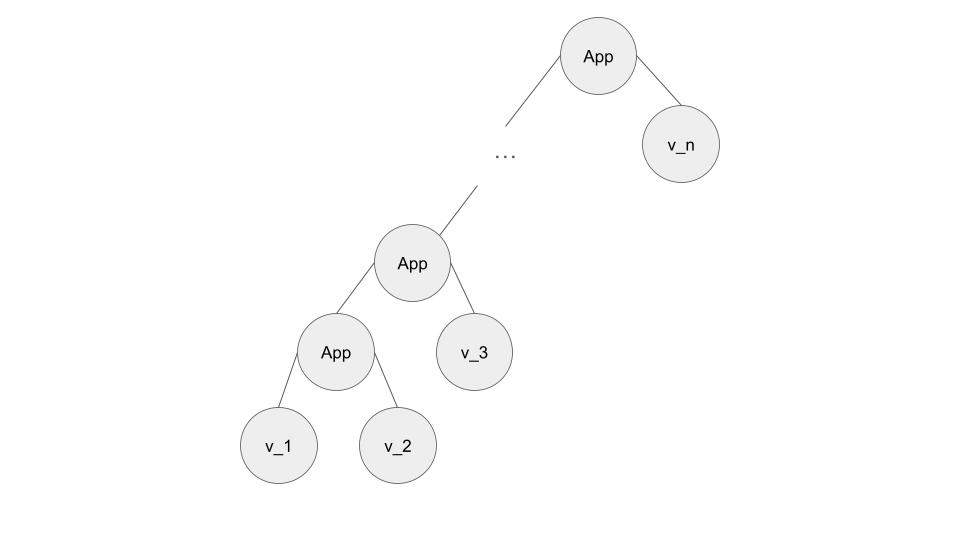

However, a key issue is that this grammar is right associative, not left associative as we had wanted. I tried for a long while to come up with a grammar that was not left-recursive but that was left-associative, but was not able to find one. In fact, I have a feeling that this might be impossible. To see this, say that there is a non-left recursive grammar that does this, and that contains nonterminals. Consider the string , which we want to parse as . . We want the parse tree to look like this:

The leaves of this parse tree are terminals, and the interior nodes are nonterminals. Let be the nonterminal that is the lowest common ancestor of and . It must be the case that if the grammar is not left-recursive. This means that contains at least nonterminals, contradicting the assumption that contains nonterminals.

Luckily, this does not mean that we need to give up on recursive descent parsing for this use case. We can just fudge the implementation so that after the parser matches a string conforming to the production , we rewire the parse tree to make it left associative instead of right associative. My final implementation does this by parsing the atoms forming a function application chain in a loop, and at each iteration, merging the newly parsed atom into the tree built so far in a left associative fashion (sidebar: I was initially doing a recursive approach to rewiring that, while functional, didn't feel super clean; Gemini 2.5 pro suggested the loop approach 😅).

Execution Engine

Overview

The execution engine was probably the most challenging part of the project, largely due to some protracted battles I had with Rust's borrow checker. Here is some pseudocode summarizing what the execution engine needs to do:

// Main execution engine functionality.

def main_functionality():

While the root is a function app and we made a change on the last iter:

Recursively evaluate the function side of the application.

Check if the function side after evaluation is a lambda abstraction.

If it is a lambda abstraction, call perform_beta_reduction.

// Substitute instances of var_name in left_expr with right_expr.

def perform_beta_reduction(left_expr, var_name, right_expr):

match left_expr:

case FnApp(e_1, e_2):

perform_beta_reduction(e_1, var_name, right_expr)

perform_beta_reduction(e_2, var_name, right_expr)

case FnDef(x, fn_body):

if x == var_name:

return

if $x \in free_vars(right_expr)$:

perform_alpha_conversion(left_expr)

perform_beta_reduction(fn_body, var_name, right_expr)

case Var(x):

if x == var_name:

copy right_expr into the tree

While developing the execution code, I first implemented a version that would perform a deepcopy of the entire AST each time it reduced a redex. This is obviously inefficient, but this was the easiest approach I could implement while adhering to Rust's borrowing rules. In a second pass, I optimized the implementation to reduce copying. The final implementation revolves around three key functions:

/// Performs lazy evaluation of a given lambda calculus expression until it is

/// in weak-head normal form. Returns a Box holding the evaluated expression,

/// and a boolean saying whether the result is different from the input

/// expression.

fn eval_expr_lazy(

mut expr_body: Box<ExprNode>,

def_statement_map: &HashMap<&str, &ExprNode>,

verbose: bool,

) -> (Box<ExprNode>, bool)

/// Performs beta reduction on expr_body, substituting instances of var_name

/// with var_value. Performs alpha conversion while doing substitutions if

/// needed.

fn perform_beta_reduction_helper(

expr_body: &mut ExprNode,

var_name: &str,

var_value: &ExprNode,

value_free_vars: &HashSet<&str>,

) -> ()

/// Given an ExprNode, a formal param to rename, and the free variables of a

/// value being substituted into the ExprNode, rename the formal_param so that

/// we don't accidentally introduce new references to the formal_param.

perform_alpha_conversion(

formal_param: &str,

fn_body: &mut ExprNode,

value_free_vars: &HashSet<&str>,

) -> ()

By having perform_beta_reduction_helper and perform_alpha_conversion take mutable references to ExprNodes, we can mutate the underlying data and avoid copying the entire AST each time.

Some Borrow Checker Difficulties

One challenge in the implementation was eval_expr_lazy. Specifically, in this function, we pattern match on a mutable reference called expr_body (the expression we are evaluating), and if it is a function application, we pattern match on a mutable reference to the function. If the function is a function definition, we need to perform beta reduction because we are at a redex. Lastly, we need to reset the expr_body pointer to be the pointer to the function definition. But since the function definition is behind a mutable reference, and since we have not taken ownership of the value when pattern matching, we cannot just dereference it and assign it to expr_body via for example *expr_body = **defined_fn. We could just take ownership of defined_fn when we pattern match instead of keeping it behind a mutable reference, but then in all cases, we will have to 're-construct' the expr_body value to move ownership of the data back into expr_body from the variables we bound during pattern matching; this is stylistically pretty awkward to do. The solution ended up being to use Rust's std::mem::replace function, which allows you to replace the data behind a mutable reference with some other data while taking ownership of the original data. This way, we can keep all pattern matching behind mutable references, but when we have to update expr_body, we can do so via expr_body = std::mem::replace(defined_fn, dummy_value()). See the code here to learn more.

Theoretically Characterizing Execution Efficiency

How do we theoretically analyze the efficiency of the execution functionality?

One option is to try to give the worst-case asymptotic complexity of reducing redexes in an expression starting with nodes. Unfortunately, I believe that any lambda calculus interpreter is going to take time exponential in the number of redexes to reduce. This is because we can write lambda calculus programs whose size grows exponentially with the number of redexes applied. Here's one that I was able to come up with:

This grows exponentially because after reductions, the expression will look like , where e has at least size .

As a base case take k = 0; we have e = a of size = 1 as required.

For the inductive step, assume the inductive hypothesis that e has size after 2k reductions. We will show it has at least size after reductions. To see this, note that

We see that has become , and since we start off with where is a free variable, this term will just keep doubling in size as required. This shows that for any lambda calculus interpreter, the worst-case complexity for performing reductions is at least .

The asymptotic analysis above is not so interesting because it reduces all implementations to having basically the same complexity. It also drops constant factors that may be useful to think about when considering the relative performance of one implementation or another.

Instead of looking at asymptotic complexity, let's try to characterize the interpreter's efficiency by counting the approximate number of operations performed for ONE reduction. For reducing a redex where has nodes, has nodes, and the substitution variable occurs times inside , the best case cost with sharing is something like because we have to traverse to find occurrences of the reduction variable, and for each occurrence, we need to rewire a pointer so that it points to now. Without sharing, the best case cost is something like because we need to copy for each of the instances of the formal parameter. In my implementation, if we are performing a reduction that does not need alpha conversion, about operations will be performed, in line with the best-case non-sharing interpreter. However, if alpha conversion is needed, we will need about operations, where the extra comes from needing to traverse the tree and rename variables as part of alpha conversion. This gives further insight into how extending the current implementation could speed up performance: using De Bruijn indices will eliminate the additional ~ operations needed to perform alpha conversion, and using sharing will eliminate the term.

Final Thoughts and Future Work

I thought this was a really fun project to work on; I learned a lot about the lambda calculus, functional programming, and ownership systems.

There are a lot of further extensions I'd like to make on this project. Firstly, I'd like to do a thorough exploration of how to implement the most performant execution engine possible. I'm hoping to build on this project to experiment with De Bruijn indices, sharing, alternative heap allocation techniques, and graph reduction machine approaches. I'd like to do a follow-up blog post giving some theoretical and empirical results comparing these methods' performance. Besides this, I'd soon like to add types, polymorphic types with let bindings, a dedicated Y combinator primitive to maintain Turing completeness with types, and more, so stay tuned!